Founder Lesson

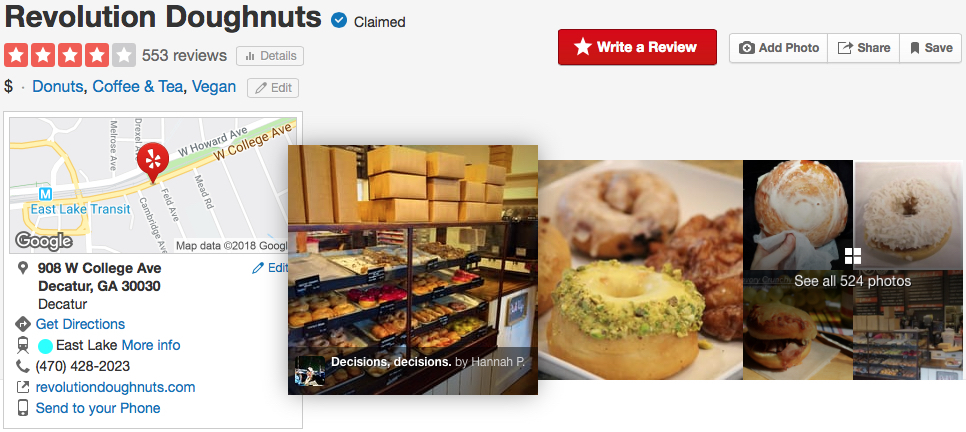

There’s a doughnut shop in my neighborhood called Revolution Doughnuts. As a neighbor I can attest that they are a tremendous local success story and their ratings on Yelp put them in the top 15% of all restaurants in town.

I lived nearby before they launched their first location, so I saw how the owner executed her launch...

Step #1 - Revolution began at a local farmer’s market. The owner would set out a basic card table and then the long lines would form. You can always tell the most popular stalls at farmer’s markets and nothing compared to Revolution...they consistently had the longest lines. This is how Revolution began to build a loyal customer base.

Step #2 - Then the owner decided to launch a Kickstarter campaign back when Kickstarter was very new and unproven. That platform allowed her unique vision to shine and she exceeded her goal by 23%. I also suspect that the extra $12k wasn’t nearly as important as using Kickstarter to build even more early, loyal fans.

Step #3 - Only after a successful Kickstarter campaign did the owner decided to open her first retail store. I was fortunate to live within walking distance to this location and there were lines out of the door every day.

Step #4 - After a few years of having a hugely successful single location, the owner of Revolution Doughnuts decided to expand to another location.

I’ve never asked Maria (the owner) this question, but I suspect there was a step even before all this...

She made one doughnut

Given how intentional Maria was with her path, I suspect that before she ever put up that very first card table at that very first farmer’s market she made doughnuts for trusted friends to gauge whether her doughnut was below average, average, pretty good or at the level of “holy shit...you gotta open a doughnut shop!”

I would call this exercise - including the farmer’s market table - “testing the inherent value of her doughnut.”

Almost without exception when I meet with first-time founders they try to think about their business as if they were Maria starting with a dozen shops from the very beginning. They delusionally assume that their doughnut is “holy shit” amazing before even having one person eat the doughnut, so they proceed to think about things like...

Raising lots of money. "How will I finance a dozen doughnut shops? Friends/family and local rich people (angels) can only fund me so much, so I’ll need to start talking with VCs from the start. That will mean lots of trips to the west coast, but that's how the best startups are funded."

Building too many features. "Since we’ll have lines out the door at a dozen shops from the start, we’ll likely need a mobile app to do mobile ordering and pickup. Also we probably need to launch with a super buttoned-up brand because we could start franchising soon. And what about a private room on the side for events at each location...with lines out the door from the start, we'll be the center of neighborhood activity, so better put that into the store plans."

Lack of activity. "Since we'll launch with this type of scale, many months of planning and financial modeling are a way better use of time than going to farmer's markets and talking with lots more customers. That's thinking way too small. We should probably also get a headstart on large-scale distribution partnerships (since we’ll need a lot of raw ingredients for a dozen shops) and hiring (since we’ll need ways to hire hundreds of employees for a dozen shops)."

Starting a dozen locations is a different path than cooking ten doughnuts or buying a card table and heading out to a farmer’s market this coming Saturday. These two paths aren’t just different...they are entirely different.

Launching a dozen locations at the start assumes things that might not be obvious to first-time founders.

For one it assumes that your doughnuts is “holy shit” amazing. Not just “yeah...this is a decent doughnut”...it assumes “holy shit...you gotta open up a doughnut shop right now!” Because of this assumption, there’s no real reason for the founder to talk with any customers, avoiding super important early feedback about all parts of the business (not just the taste of the doughnut). And not talking with customers means that you aren’t building the early tribe that will be your early, loyal customer base. Starting with a dozen locations from the start means focusing on entirely different challenges like financing and scale issues.

For those not familiar with the differences between small businesses and high-growth business, read this foundational essay on the topic. Simply put, small businesses (like a doughnut shop) grow at different rates than what we all traditionally call “startups.”

As a result of this growth rate, being intentional like Maria is a good practice for a small business, but mandatory for high-growth startups.

If you think back to the origin story of high-profile startups you’ll be able to pick-out the moments when the founders were testing the inherent value of their doughnuts...

Uber - The founders famously shared the phone numbers of a few black car drivers in SF and only thought of creating a two-sided marketplace when their friends were using these cars all the time. The Uber doughnut...the phone number of a few local black car drivers. Level of effort for this test...super low.

Airbnb - The founders famously put their SF apartment on Craigslist during a sold-out conference weekend. I’d call this “making doughnuts for ten friends.” Then they intentionally faked the supply side in NYC to see if people would stay in the homes of strangers. I’d call this “putting up a card table at a farmer’s market.” The Airbnb doughnut...having strangers stay in their apartment one weekend. Level of effort for this test...low.

Tinder - The founder manually got the app into the hands of men and women at fraternities and sororities on the campus of SMU to test their reaction to the innovative notion of swiping right & left. The Tinder doughnut...one hundred students using a beta app. Level of effort for this test...higher than Uber or Airbnb, but not more than 50 hours of development work on a beta app (if the app is solely focused on testing this human behavior).

I meet with lots and lots of new founders and I’ve now tried to start seven startups myself, so I understand the delusion of first-time founders. They are the target customer and this idea has been in their head for months or years. Their smart friends - who are also the targets customers - have told them for years that they should quit their jobs and do this. And over time they’ve gotten many other antecdotal signs (usually confirmation bias) that this will work, so the founder learns to ignore all naysayers. Then the founder quits their job to work full-time on this idea, further strengthening their resolve in launching with a dozen doughnut shops at once. Taken together this all forms a delusion that's almost impossible to fight. I get it...I try to fight this delusion with new founders on a daily basis.

(btw I also understand that this delusion is super important and super mandatory for this journey because the odds of success are so poor)

Sometimes when I make this argument to first-time founders they’ll say something like “oh...I’ve talked with dozens of potential customers, so I know my doughnut is amazing.” I cannot stress this enough...customer feedback has very little value in the early days (reasons here and here). The only way to know if your doughnut is good is to have someone eat (experience) it.

This is what Airbnb, Uber & Tinder did in the above examples. I’m sure those founders talked with dozens (or hundreds) of people about their concepts. While these conversations are helpful, they are not the same as having customers try their doughnut.

What I encourage new founders to try and understand - even though it typically takes 9-18 months to understand this lesson and get past the early delusion (if it ever happens) - is that the simple act of seeing if people “love your doughnut” has to be their first step because it guides all future steps. Plus - if their delusion is exactly right - they’ll get early “lines at the farmer’s market” with their very first test. These results - from "holy shit!" feedback from trusted friends to lines of strangers at the farmer’s market - will have important ripple effects on things like morale of the team and excitement of potential investors. So why not do it?

I think of it like a person shooting a bow and arrow. When the arrow is pulled back, but still against the string, even very slight movements in your hand will have huge differences in the ultimate destination of your arrow once it’s shot (eg moving your hand an inch to the right could alter the destination of your arrow dozens of feet once it reaches the target).

Just like this, early conversations with trusted friends and people at the farmer’s market aren’t just “nice to haves” with new startup ideas...they are mandatory on your path to something potentially big because of their ripple effects on everything in the future.

This podcast caught my ear when the founder discussed testing her new product...a re-invented shower cap. For 18 months she created a bunch of new physical caps to wear in order to know if her design was truly better than what existed. Unlike other designers, she used sample rooms to develop prototypes...not just final products after a super long design process (the traditional path). This iterative approach is similar to how digital apps are prototyped by the best founders and a great example of a founder making one doughnut (at a time).

If you are a first-time founder you are likely to think about your app at scale...when everything in the universe is humming as you expected. You'll be well served to test the inherent value of your customer value prop (doughnut) as early and quickly as possible. You just can't skip steps.

Sidenote: If you enjoyed this post, you might like this one as well.

Get Right to the Lesson

I’d recommend listening to the entire thing, but to get right to the point go to minute 13:01 of this podcast.

Thanks to these folks for helping us all learn faster

Jacquelyn De Jesu (@deejayzoo), founder/CEO of SHHHOWERCAP (@SHHHOWERCAP)

Loose Threads (@loosethreadscom)

Richie Siegel (@rsiegel)

Please let me and others know what you think about this topic

Email me privately at dave@switchyards.com or let's discuss publicly at @davempayne.

The best startup advice from experienced founders...one real-world lesson at a time.